As we ended 2024 and began 2025, EST mourned and remembered Richmond Hoxie.

Richmond was an actor of singular charisma, capable of summoning wild comedy and genuine menace, even within the same scene. In performance and rehearsal and in his everyday life, he brought intense dedication to his craft, cut with a wry, observant sense of humor and surprising tenderness. Richmond created performances no one else could, again and again, from the theatre’s first decade right up through its fifth.

Richmond died just before Thanksgiving. He was 78.

As people heard of his passing during the holiday season, different generations of EST were hit hard by the loss. Richmond’s career extended beyond EST, but when he was here, and you were here, he was part of how you knew the place.

Zach Grenier remembers the first time he ever saw him. “My wife Lynn and I saw him onstage at EST, in Landscape With Waitress, a play by Robert Pine with Richmond and Wende Dasteel. This was in I guess 1981, and it was an extraordinary performance, a pastoral piece that expanded into this beautiful fantasy.

“We saw Richmond and we said, ‘oh my God, who is this guy?’ So we waited in the lobby afterwards and introduced ourselves. And then we were friends for 40 years.”

That play was an early instance of the impression Richmond built with audiences and critics. Mel Gussow singled him out in the New York Times, commending his “gusto” and calling him “an open book of imaginary conversations and glamorous delusions.”

Gussow’s admiration of Richmond in the Times continued for years. In 1979 he praised his “series of deft, comic portraits” (in Neal Bell’s Operation Midnight Climax); in 1983 he called him “a master at expressing idiosyncrasies” (in Bill Wise’s Two Hotdogs With Everything at EST); and in 1989 (for Bell’s Sleeping Dogs), Gussow expanded further: “As he has demonstrated on a number of other occasions, Mr. Hoxie is an expert at mocking stuffed shirts.”

Peter Maloney directed Richmond for the first time in 1980, in Slab Boys by John Byrne.

“I cast some other guy and ended up firing him on the first day of rehearsal. And then here was Richmond Hoxie, exactly what I needed. I never once cast him and regretted it, ever.”

33 years later, Peter cast Richmond in Murray Schisgal’s Marathon one-act Existence. In that play Richmond paired with Kristin Griffith, his partner on many stages over the decades.

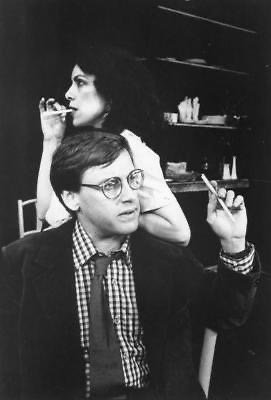

Richmond Hoxie with Wende Dasteel in Landscape With Waitress (1981)

“I remember Richmond, with his suspenders,” said Kristin, teasingly referencing Richmond’s signature style choice. (Less formally, he’d often sport a fishing vest.) “He had that very sly sense of humor, a kind of low undercurrent way with his lines. He had a great deal of grace about him, and was very generous onstage.”

“He was very serious about the work,” said Peter. “He could be somewhat enigmatic.”

“Did you know he was a composer?” said Kristin. “We did The Long Christmas Dinner by Thornton Wilder and he ended up doing the musical direction for that, and for a few other plays.”

“He loved music,” affirmed Zach. “A consummate musician. He had a piano in his apartment. He composed for a Dracula musical once. If music was playing – he’d still be sitting in the room with you, but in his mind, he left the room and went to the music.”

Richmond’s inimitable voice also brought him success in voiceovers and audiobooks – particularly the works of Milan Kundera, including The Unbearable Lightness Of Being. And he was a gifted director, particularly with A Blooming Of Ivy, a lovely piece by Garry Williams from the 2003 Marathon, featuring Jim Rebhorn and Phyllis Somerville.

But it was as an actor that people knew Richmond best: on Broadway in I’m Not Rappaport; regionally doing Shakespeare at Hartford Stage and the McCarter, Tennessee Williams at A.R.T., Arthur Miller at Hartford; and in both All the Way and The Great Society at Arena Stage, as J. Edgar Hoover. On film he was in JFK and In The Still Of The Night; on TV he did All My Children, LA Law, Boardwalk Empire and the first three Law & Order series.

Even with those credits, his work at EST looms large. Among many, many others: To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday by Michael Brady, from 1983, was one of the theatre’s first transfers, with a long run at Circle In The Square; Louis Slotin Sonata by Paul Mullin, from 2001, was a key play in the early days of the EST/Sloan Project; and Lenin’s Embalmers by Vern Thiessen, from 2009, featured Richmond’s remarkable portrayal of Joseph Stalin. Directed by Billy Carden, that cast included Peter and Zach, and both remembered his fondness for that play, and that role.

“His apartment on Thompson Street was lined with bookshelves,” chuckled Zach. “Everywhere you looked were books, and records…and that picture of Stalin.”

“We both got them from the set,” added Peter. “I got Lenin and he got Stalin. And he kept it!”

Pam Berlin directed Richmond often in his early career, including To Gillian. “I remember that apartment was full of books and records, even then,” she said.

“I also remember a story I heard about Richmond,” she added. “From the time of To Gillian. It was late in the run, I wasn’t there – but it was at curtain call, and the audience were cheering, on their feet, but that day people didn’t want to go back out. Two-show day, late in the run, who knows why. But Richmond stood up and said, ‘Listen to that audience! We owe it to them, to go back out there, to acknowledge their applause. It’s our duty, as actors.’ He took that very seriously. And I’ve never forgotten that.”

Richmond’s close friend Garrett Brown remembered him in writing:

The company of To Gillian, On Her 37th Birthday (1983) - clockwise from upper left: David Rasche, Noelle Parker, Cheryl MacFadden, Pamela Berlin (director), Richmond Hoxie, Sarah Jessica Parker, Frances Conroy, Jean DeBaer, around seated playwright Michael Brady

“Ensemble. Studio. Theatre…Hoxie was all that—a colleague, a worker, a fellow compadre, and like me, part of the “Ensemble”; “Studio”, as in the artist’s studio, and as part of studying: working on stage with Richmond (we did Bill Bozzone’s Touch Black and Bill Wise’s Two Hotdogs with Everything), a delight, intent on serving the play and ever present, in the moment as partner, co-creator. But, the studied part: maybe since he was a composer and lover of music, I realized it the night I saw Hox and Paul Austin in Percy Granger’s Vivien, both of them vivid, powerful. Hoxie’s performance was so full, rich, so specific—and—so orchestrated, not pro forma, but as music is filled with that inner structured solidity that then gives off these delicious flourishes and surprises; which brings me to “Theatre” with an “-re” ending, not the convenient and Americanized “-er”—Hoxie was of the traditional, hard-won, timeless and timely—Theatre—and what a joy and gift to know him, love him, and love working with him.”

All of us at EST send our sympathy to Richmond’s wife, Bonnie; to his friends and loved ones; and to everyone who worked with him onstage, who heard him speak their words, or who ever got to be in a room with this artist, bearing witness to his art.