On Tuesday, February 19, as part of the 2019 First Light Festival, the EST/Sloan Project is presenting the first public reading of THE BIOLOGY OF THE SURFACE by Dominic Taylor. The play dramatizes the working relationship -- and romance – over some ten years in the 1920s and 1930s between the pioneering African American biologist Ernest Everett Just and one of his students, Roger Arliner Young, who went on to become the first African American women to earn a doctorate in zoology. The playwright uses this relationship to mine rich themes about eugenics and racism in the sciences during that time, power dynamics in academia and scientific publishing, the design of experiments, and the costly unknowns of some technology. But let’s hear more from the creator.

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

What moved you to write THE BIOLOGY OF THE SURFACE?

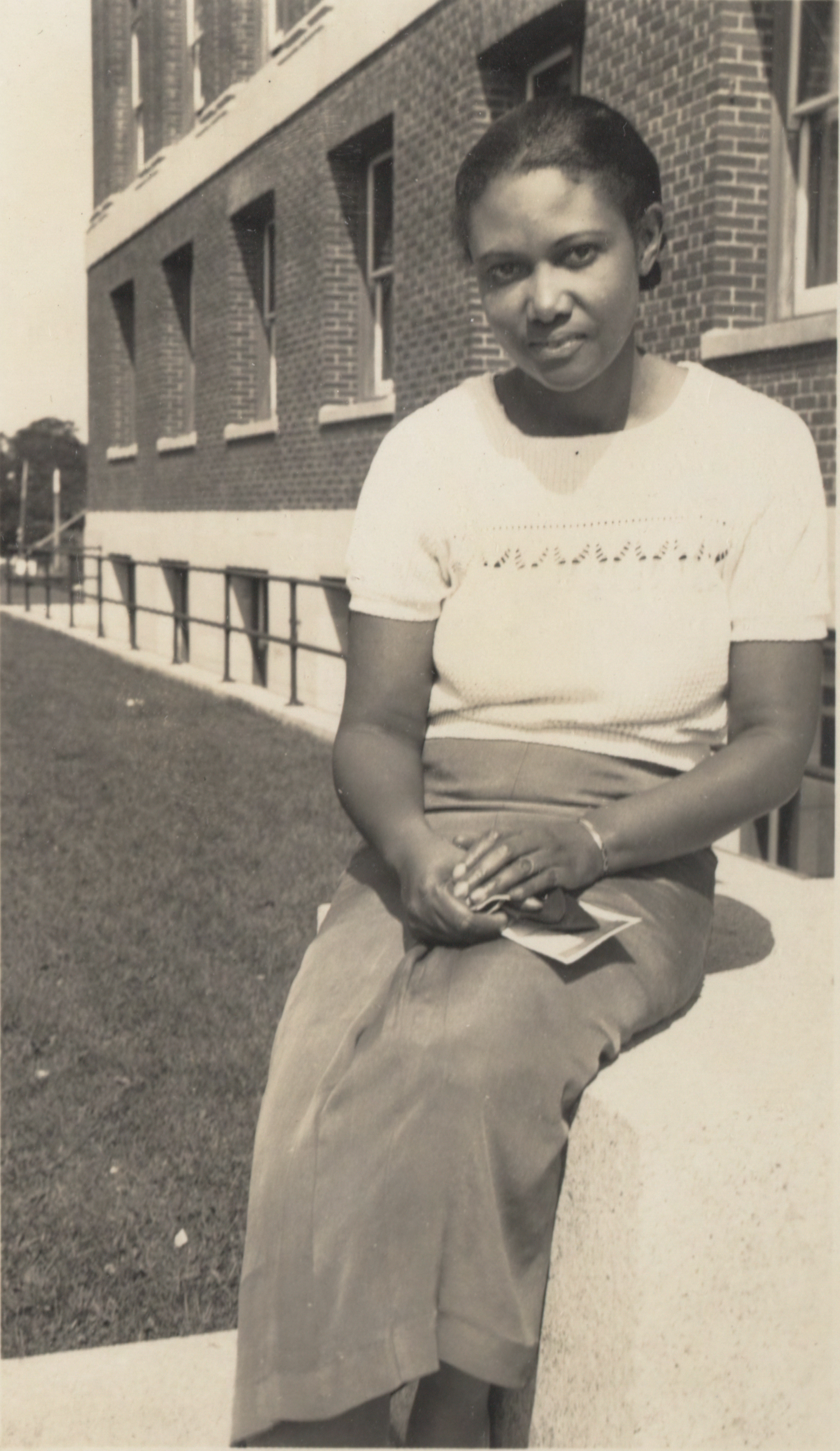

I knew something about Ernest Everett Just but not a lot. I knew that he was the first African American graduate of Dartmouth College. I knew that he was a major thinker in biology at the beginning of the twentieth century. As I researched him, I learned that he worked for a long time with a graduate assistant Roger Arliner Young. When I discovered that Roger Young was a woman, I become more intrigued, especially in that she is not mentioned in his seminal text The Biology of the Cell Surface.

Why this play? Why now?

There are a few reasons. The first has to do with class. Class in the African American community is never examined. People often assume that there is no way that a black woman could earn a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in the 1930s. Young did. The nature of the African American poor or working-class woman and man is replete in many works. This play allowed me to address many questions: class, gender, mentor-mentee relationships, and academic life. These areas are seldom examined in any African American context.

What research did you do to write your play?

Primarily, I read texts. Black Apollo of Science, by Kenneth Manning, is the primary biography of Just. One of the things I noticed was that it did not examine the collaborative nature of scientific study. This is where I met Roger Young. How could this young woman be a research assistant for seven years prior to the publishing of The Biology of the Cell Surface but not be mentioned in the book at all? I have a background in the sciences. My undergraduate degree is in engineering, not biology, but I think it helped my understanding of the play. I adopted a different type of three-act structure: a hypothesis, an experiment and then data analysis.

The action of the play takes place at Howard University in D.C. and at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts in the twenties and thirties. What should the audience know about the environment in which Just and Young were doing research at that time?

There are so many things, but perhaps the most significant might be how different African American life was in the 1920s and 1930s. The 1920s was a period when with the end of WWI and the Great Migration, black life changed. It was the time of the Harlem Renaissance and the birth of the work of Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes. It was also a time when Ida B. Wells was writing every day about the lynching of African Americans. Lynching was legal into the 1940s. Additionally, the 1930s was a time when after the Great Depression, the limited economic gains of African Americans had been pushed back.

In the play one matter of contention between Just and Young is how much she contributed to his most famous work, The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939). Is there evidence he failed to acknowledge her contribution?

This is a fact. There is no mention of this woman in anything referencing this book. Not in a foreword or an acknowledgement page. There is no indication of her contribution anywhere. Additionally, she was removed from Howard University’s faculty just before the book was published. The reasoning offered in Black Apollo of Science was that Just wanted to stand alone alongside other singular scientists. Percy Julian and Charles Drew on Howard’s faculty are also notable in this regard, but this was true of all scientists at the time. Who was Thomas Alva Edison’s assistant or Alexander Graham Bell’s? Scientists at the time believed they must stand alone as singular titans of brilliance.

Your play has three sections that take place in 1926, 1929 and 1936. Quite a lot has changed between the two characters between 1929 and 1936. Young has failed her dissertation defense with Just’s mentor, Frank R. Lillie, at the University of Chicago. Her eyesight has become damaged from her work with ultraviolet radiation in Just’s experiments. Just is about to get married for the second time, to a white German woman, and there is evidence that at this point both have been actively engaged in sabotaging the other’s career. Is it likely such a scene ever happened? How did everything go so wrong?

One of the fun things about research is putting puzzle pieces together. Reading about Young, (a good text to start was Black Women Scientists in the United States by Wini Warren) I learned that her vision did deteriorate over time. The ultraviolet lamps she used for Just’s experiments were unsafe. The knowledge of light therapy and early X-ray technology was limited and no one knew the complete damage. Black Apollo of Science also tells us that Just wanted to get his new would-be-wife a job at Howard. Howard’s president, Mordecai Johnson, was appalled at what he heard about the behavior of both Just and another scientist Percy Julian while they were in Europe. Both men were married but engaged in inappropriate behavior abroad. Johnson needed to rein in this behavior.

Stephen Jay Gould has written about his obsession with the photo of Just at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, where Just worked for some twenty summers. Gould describes the photo: “The man it depicted was singularly handsome, with a pervasive look of sadness that touched me across half a century.” He goes on to characterize Just as “fascinating, complex, and ambiguous,” “If he had fit the mold of an acceptable black scientist, he might have survived in the hypocritical world of white liberalism in his time. A man like George Washington Carver, who upheld Booker T. Washington’s doctrine of slow and humble self-help for blacks, who dressed in his agricultural work clothes, and who spent his life in the practical task of helping black farmers find more uses for peanuts, was paraded as a paragon of proper black science. But Just preferred fancy suits, good wines, classical music, and women of all colors.” What’s your take on Just?

Gould is accurate in how I saw Just as well. Just did not want to be constrained by teaching only at Howard. He applied for positions at Brown and Dartmouth and was rejected by both. He wrote about wanting to teach at a major research institution. At the time this was a euphemism for a white institution. Gould’s description of him not willing to sublimate himself is apt. In my reading of him, he was a very complex modern man, and I hope I show that complexity in the play.

What do you want the audience to take away from THE BIOLOGY OF THE SURFACE?

First, I want them to meet these two titans of science. Second, I want them to consider how they should have interacted. On the surface, a brilliant black man and a brilliant black woman should have helped each other achieve degrees of success. The fact that each had success in his and her own right is good to know, but the success could have been exponential. How did race or pressure around race, science and the academy hinder this understanding? I also want the audience to consider the mentor/mentee relationship. How it operated on and beneath the surface.

Just was ahead of his time in viewing the organisms he studied as part of an ecosystem and that the cell surface represented an organizational complexity that could not be reduced to the sum of its parts. Do you see a connection between Just’s “holistic” ideas and the way he behaves in his relationship with Young?

I think he could not see the relationship completely. He had a blind spot. A bad analogy might be Louis CK championing women comedians, yet engaging in behavior that was inappropriate. If he could have seen her contribution as part of his ecosystem, he could have helped her in a series of career ways that he chose not to do. The personal relationship presented in the play is speculative, but we know he did not buoy her career and he could have. He was looking at a tree and not the complete ecosystem.

Young’s work with Just impaired her vision for the rest of her life. When she failed her defense of her PhD dissertation at the University of Chicago, Frank Lillie (who had been Just’s mentor) would no longer work with her and Just effectively abandoned her and eventually got her fired from Howard. Young never married. After she left Howard, Young struggled to find work and later checked herself into a mental institution and died impoverished. In this #MeToo era, can’t the case be made that Just was a monster who used and destroyed his mentee Young?

Not necessarily. After being fired from Howard, Young went on to get her PhD from the University of Pennsylvania (1940). She taught at North Carolina College for Negroes in the 1940s. In 1944 she helped the NAACP register voters. Her activism got her blacklisted from teaching in North Carolina. She had to go to Jackson State in Mississippi to teach after that. She committed herself in 1962, more than 20 years after Just died. After leaving the mental institution, she went on to teach at Shaw University in Louisiana.

The fact that she died in poverty was an outgrowth of her bad health and a series of additional events in her life that I do not dramatize.

I guess that the case could be made that Just was a monster, but I am hoping that the audience leaves with a more complex view. We knew so little about the effects of UV light in the 1930s.

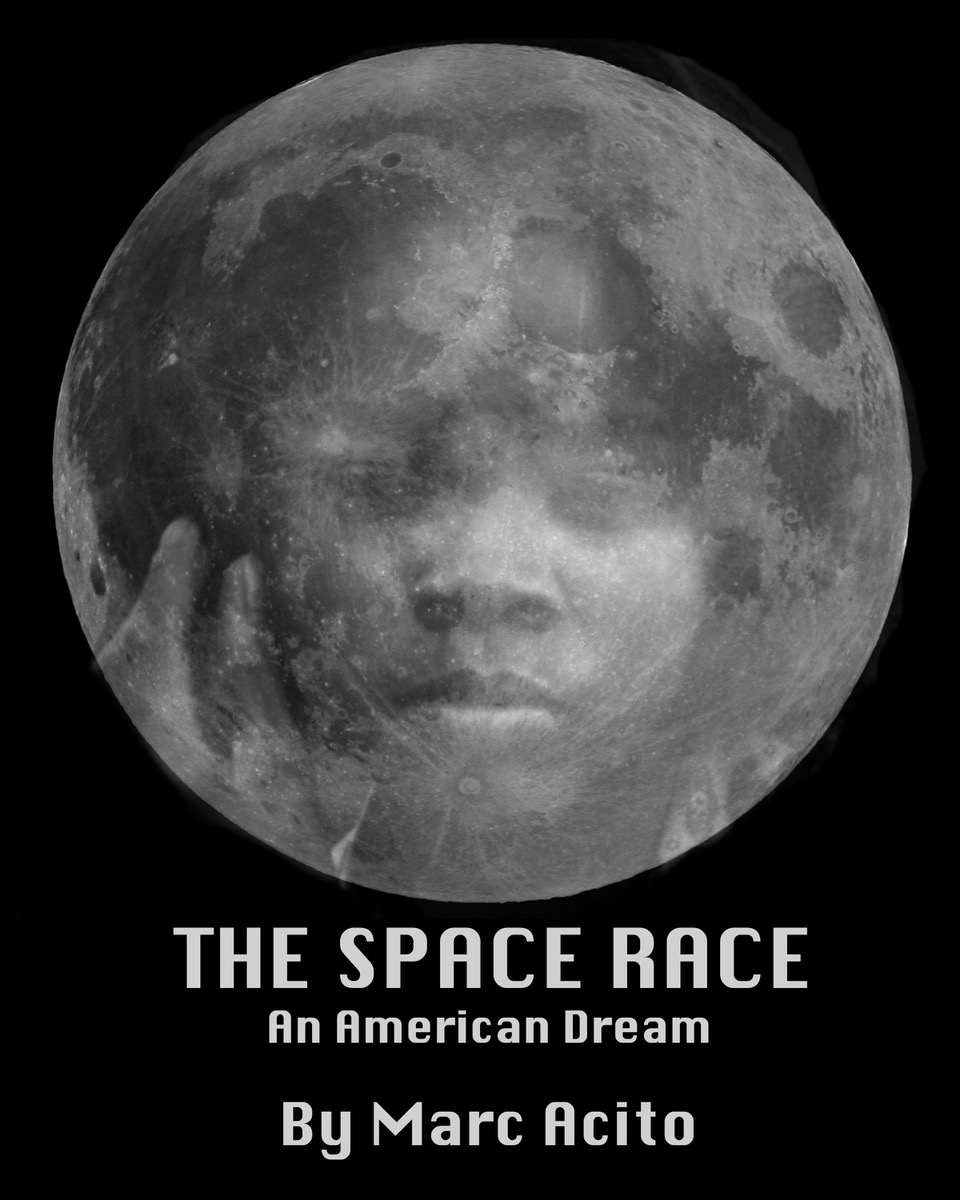

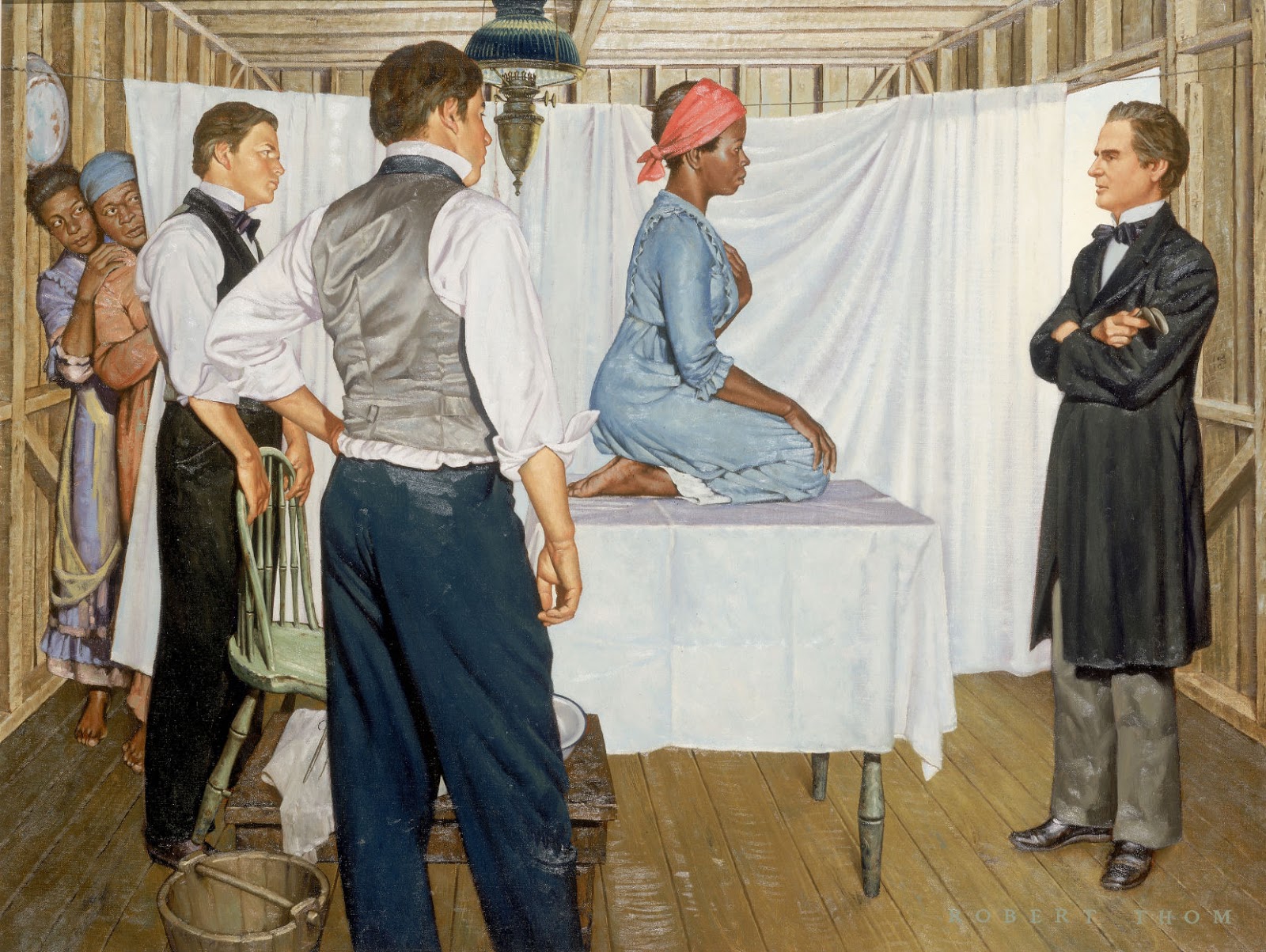

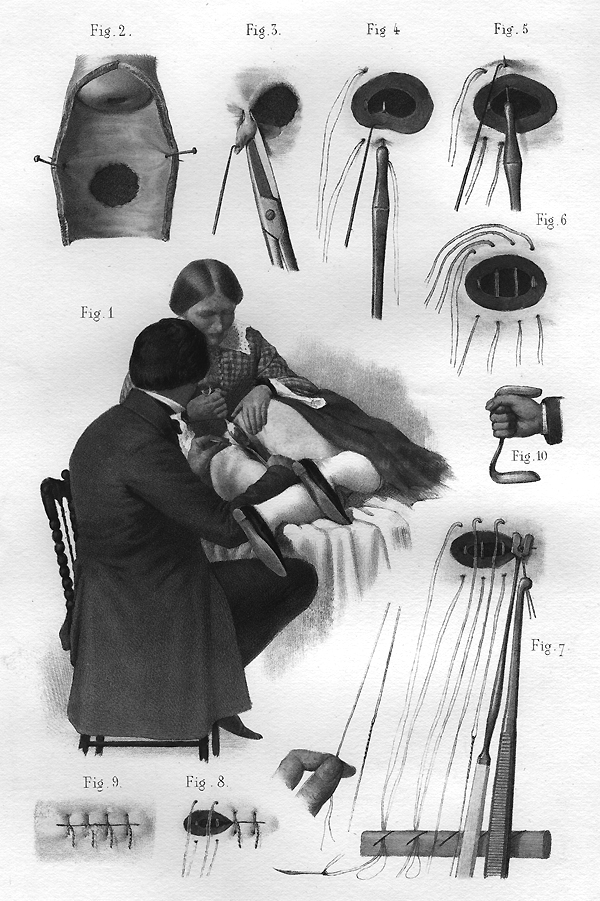

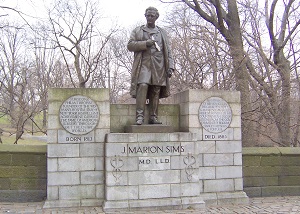

The 2019 EST/Sloan First Light Festival runs from January 28 through March 1 and features readings and workshop productions of ten new plays. The climax of every EST/Sloan season is the annual Mainstage Production, which this year was the world premiere of BEHIND THE SHEET by Charly Evon Simpson. Directed by Colette Robert, BEHIND THE SHEET confronts the history of a great medical breakthrough by telling the forgotten story of a community of enslaved black women who involuntarily enabled the discovery. Previews began January 9 and the show runs through March 10. Tickets can be purchased here. The First Light Festival is made possible through the alliance between The Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, now in its twentieth year.