On Monday, January 28, as part of the 2019 First Light Festival, the EST/Sloan Project is presenting the first public reading of WHAT LOOKS LIKE PRETTY, Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder’s new play about the intersection of race, the science of capturing images, and business ethics. When an African-American girl goes missing in 1963, colleagues Gloria and Charlie struggle to get a photograph the police can use, and begin to question who gets seen and who is invisible.

As she traveled east from Tennessee, where she is the Tennessee Williams Playwright-in-Residence at Sewanee: The University of the South, Elyzabeth stopped a few moments to answers our questions.

What inspired you to write WHAT LOOKS LIKE PRETTY?

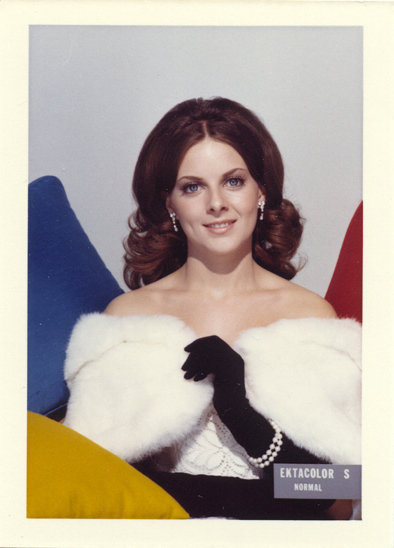

Several years ago, I read an article about the Kodak Shirley cards which had been used for color correction in the labs. The photograph was always of a fair-skinned white woman and across the bottom of the photograph they would stamp "NORMAL". It made me think about how visual representations of beauty and "normalcy" shape our perceptions and control the narrative that is created about those who might not fit within that norm.

What research did you do to prepare to write the play? Did you work with a technical consultant to get the scientific details right?

In the fall of 2017 I received a research grant to travel to Rochester to view the Kodak archives. It turned out to be a terrifying experience, because the more I read, the more I realized just how complicated the issue actually was. You have the racial bias that influenced what was created in the lab, but you also have to consider how light functions and how our eyes process color and light. I left feeling overwhelmed.

OK, that covers research on the science. How about research on the characters?

I was really struggling to find Gloria's voice in this play; then I was asked to participate in the Alabama Shakespeare Festival's State of the South tour. We put four playwrights, the artistic director, and a filmmaker in a van and spent 10 days touring the Southeast, cities and tiny towns, across Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Georgia, hosting town hall discussions about the changing face of Southern identity. American Theatre did an article on our trip. I heard so many people talk about feeling invisible in their community and the efforts being made to be seen. Those conversations really got to the heart of Gloria's struggle. You can watch many of these interviews in the video we created afterward: “The State of the South.”

You set your play in 1963? Why that year?

I really struggled with deciding on the time period. The Shirley cards have been used for years. However, the Kodak Instamatics were first released in the early 60s and that’s when color photography started to become the norm. The technology was becoming increasingly common and accessible. It was also such a volatile time in our country in terms of race relations. I thought that made for a powerful backdrop. The African-American community was fighting not just for equality, but for visibility, and here you had this new technology that was working against that. It was also a pivotal time for race relations in Rochester. The African-American population was growing and the city was increasingly divided. The following year all of that tension erupted in the biggest race riot in the city's history.

You seem to have tapped a rich thematic vein in writing a play about how photography has shaped how we see – and don’t see – each other. And how we remember. Has writing this play changed how you look at photographs? At cameras?

The way we consume photography has changed dramatically since color photography became mainstream. It is instant, it is abundant, and it can be manipulated more than ever. Now that everyone has a camera on their phone, we are seeing stories unfold from multiple angles. It's a reminder that a photo can capture an image, but it doesn't necessarily tell the whole story.

Have you written any other plays on scientific subjects?

My play, A Requiem for August Moon, was my first experience writing a play based on a scientific theory. By focusing on a Ph.D. student who develops an algorithm for predicting a hit song, it explores the relationship between art and science.

Do you have any special advice to give to someone writing a science-themed play?

The biggest challenge I always face is finding a way to blend the science with the personal. An audience isn't going to be able to invest emotionally in the science, but they will invest in a character who is wrestling with its consequences.

When did you know you were a playwright?

I spent a lot of time as a kid writing monologues and short plays. I started doing local theatre in the fourth grade and fell in love with it. I always knew I wanted to work in the theatre, but I think I was always aware that I wasn't really an actor. I saw Madeleine George's "The Most Massive Woman Wins" at the Young Playwrights Festival at the Public when I was 17 and that's when I realized that maybe I could write plays, too. Wendy Wasserstein was there that day. I worked up the nerve to talk to her and after I poured my heart out, she told me to go home and write a play. So I did.

What’s next for Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder?

I'm working on another play, The Light of the World, which explores our relationship with Confederate iconography. I'm also researching a new play about service workers at the Atlanta airport and the exploitation of minimum wage employees.

The 2019 EST/Sloan First Light Festival runs from January 28 through March 1 and features readings and workshop productions of ten new plays. The climax of every EST/Sloan season is the annual Mainstage Production, which this year was the world premiere of BEHIND THE SHEET by Charly Evon Simpson. Directed by Colette Robert, BEHIND THE SHEET confronts the history of a great medical breakthrough by telling the forgotten story of a community of enslaved black women who involuntarily enabled the discovery. Previews began January 9 and the show runs through February 10. Tickets can be purchased here. The First Light Festival is made possible through the alliance between The Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, now in its twentieth year.