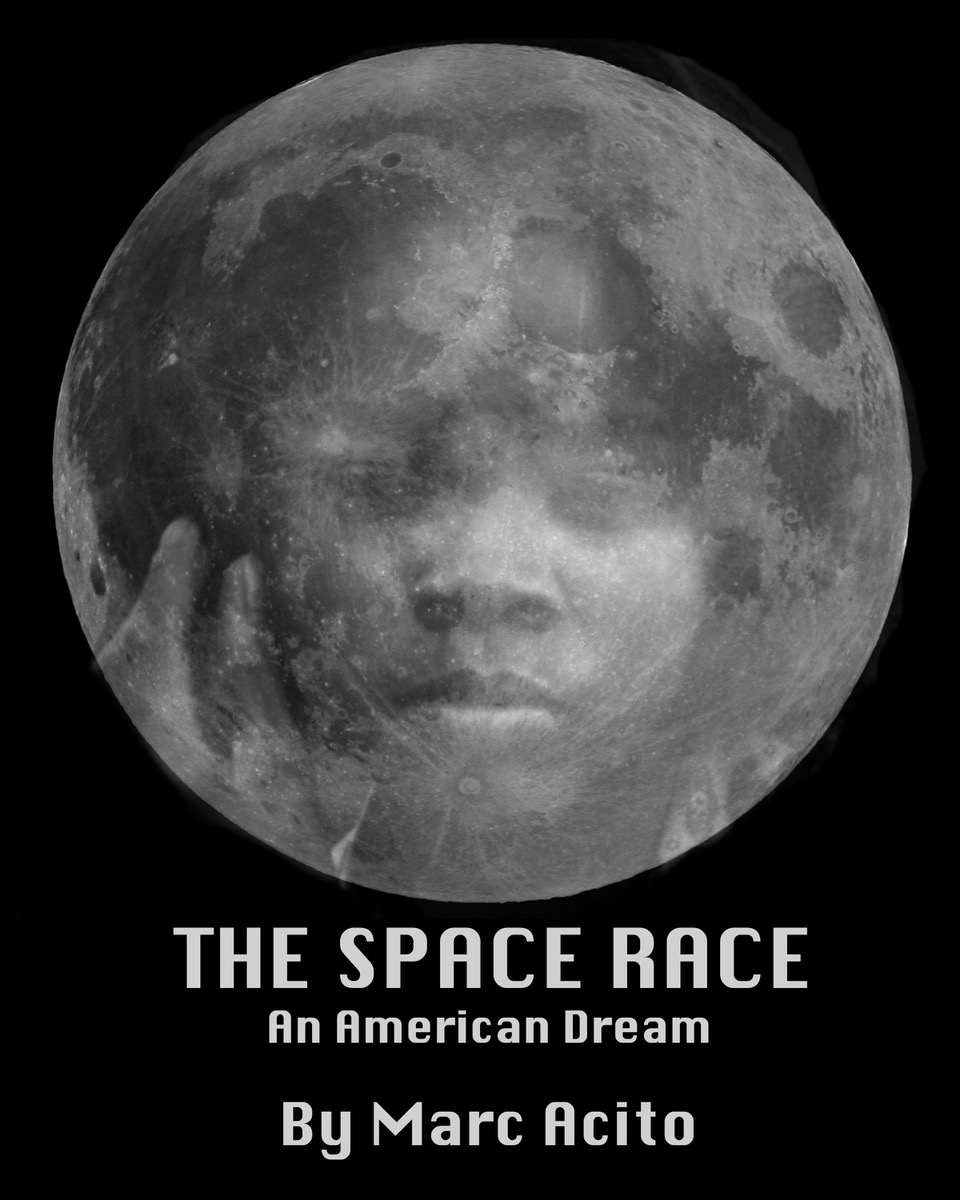

On Thursday, January 31, as part of this year’s First Light Festival, the EST/Sloan Project will host a public reading of THE SPACE RACE: An American Dream by Marc Acito. THE SPACE RACE had its first reading during last year’s First Light Festival when it had the title MAN IN THE MOON. The play opens in 1967 when 55-year-old German émigré rocket scientist Wernher von Braun is on the verge of realizing his lifelong dream of putting a man on the moon. For the past seventeen years he has been leading the development of American rocket technology in Huntsville, Alabama, first with the Army, then, in 1960, as NASA’s first director of the new Marshall Space Flight Center there . . . but this makes it sound like a straightforward story and THE SPACE RACE is anything but that. So let’s hear the playwright’s take.

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

What inspired you to write THE SPACE RACE?

In order to “win” the arms race, the U.S. military recruited Nazi war criminals and enabled them to escape justice. Our rockets to the moon were fueled with the blood of thousands. Those victims deserve justice. And the corruption of American exceptionalism demands examination.

Why this play? Why now?

With the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing this year, I expect to see a lot of misinformation from parties with competing agendas. Polls show that 7% of Americans don’t believe we landed on the moon, along with 40% of Russians and 52% of Britons. The future of democracy depends on bringing the truth to light, particularly when the veracity of verifiable information suffers daily assaults.

THE SPACE RACE had its first public reading last February as part of the 2018 First Light Festival when its title was Man in the Moon. Why the title change? What’s changed in the play? What were you aiming to do in the new version?

I chose the title Man in the Moon as a reference to Wernher von Braun, with the idea that the play was about this man who got us to the moon. But when I heard the play for the first time last year, I realized it was about much more than Von Braun. The title change reflects the widening lens.

The other big takeaway from last year’s reading was how the surreal aspects didn’t have the impact of the real. Getting those elements to register has been the bulk of my work.

Many historians claim that America could never have put a man on the moon without the vision, knowledge, and inventiveness of Wernher von Braun. Yet many also question how truthful he was in describing his involvement with the Nazi war effort during World War II, especially the use of prisoner slave labor to build the German rockets. How do you want the audience to feel about him?

Von Braun’s complicity with evil led to one of humankind’s most sublime achievements. I want the audience to discuss and decide among itself: What should the U.S. government have done? Are some minds too essential to execute? What happens when the advancement of knowledge collides with human ethics? These questions don’t yield easy answers, but hopefully they’ll inspire some enlightening post-show discussions.

The play shows sides of Wernher von Braun that audiences may be unfamiliar with: that besides being the world’s foremost rocket scientist, that he was quite the ladies’ man, a skilled musician and music lover, and that in America he had a religious conversion to Evangelical Christianity. Did anything you discovered as part of your research about him surprise you?

Von Braun was only 35 when he converted, a fact crucial to understanding his actions in America. He also married then. While he was sexually charismatic, I believe the moon was his only mistress.

What surprised me most was the dramatic unity and irony of von Braun’s experiences; I don’t want to give away any plot twists, but suffice it to say if I wrote them as fiction, you’d say they were implausible. Von Braun’s life suits dramatization because there’s just enough historical record to see the man’s dimensions but not too much to impede speculation. His story has the scope of a Greek tragedy, operatic and Shakespearean in its proportions.

One of the more chilling characters in MAN IN THE MOON is Dolf Baumgarten, a survivor of the Mittelwerk prison camp where the German V-2 rockets were built. Is he based on a historic person?

Dolf is a fictional composite based on the accounts of survivors. The harrowing events he relates are all true.

MAN IN THE MOON interweaves the story of Wernher von Braun with the lives of Glory and Fix Watson. Fix is a black engineer native to Huntsville; Glory, his journalist wife, is a native of Chicago. Were these characters based on anyone who actually worked with Von Braun? If you invented them, why?

Like Dolf, Fix is a fictional composite of the black pioneers at NASA, including Morgan Watson, who graciously allowed me to interview him. Given von Braun’s documented support of integration, I felt comfortable inventing his relationship with Fix in the absence of any account. Glory is completely fictional, though her offstage activities are with real people—the activists Dr. John Cashin and Clyde Foster.

We have so many new characters in THE SPACE RACE compared with MAN IN THE MOON: Glory now has two friends, Joan and Myrna; Maria, von Braun’s wife, is now a character; an engineering whistleblower, Thomas Baron, only briefly mentioned before, now takes the stage; and two characters, the mysterious Professor Mannfeldt and Friede, seem to have stepped out of the screen of the 1923 Fritz Lang film Woman in the Moon. And we finally have a true Wagnerian character in Erda, goddess of the Earth. What prompted you to add so many characters? Can you still work with just five actors?

We’re up to six actors now. The addition of all those roles reflects my effort to root the surreal aspects in the psychological reality of the characters. I credit Tony Kushner, who read my rewrite and encouraged me to locate the surreal landscape in the dream world of the characters.

For me this version tackles the same sobering issues as the last: von Braun’s complicity in using slave labor to build the first V-2 rockets under the Nazis; his charming, complex character; the dilemma of the black couple in considering exposing him; but the treatment, the presentation here struck me as more boldly theatrical with more music, more characters, more effects, more flights of fancy, and could there even be more Wagnerian elements in it? Was this as much fun to rework as it reads?

Welcome to my world. I reject naturalism as an artist because it doesn’t fully express my experience of life. Countless images and sounds course through our consciousness in every moment, so to see a play that only portrays people from the outside feels incomplete to me. So, yes, it is more Wagnerian—not only in its use of his operatic material, but in its conception as a gesantkuntswerk.

You incorporate some serious science into the play with discussion of the “sympathetic vibration” of the rocket and fuel tube and von Braun’s description of the “genesis of the moon.” How did you decide how much science to include in the play?

What excites me most about a narrative that requires science are the metaphors. Science allows us to understand the physical world, but its institutional language puts up a barrier best breached by poetry. In our Disinformation Age, dramatists have a moral obligation to provide and facilitate an accessible forum for ideas. Luckily, theatergoers seem to welcome an intellectual meal if it’s well-prepared.

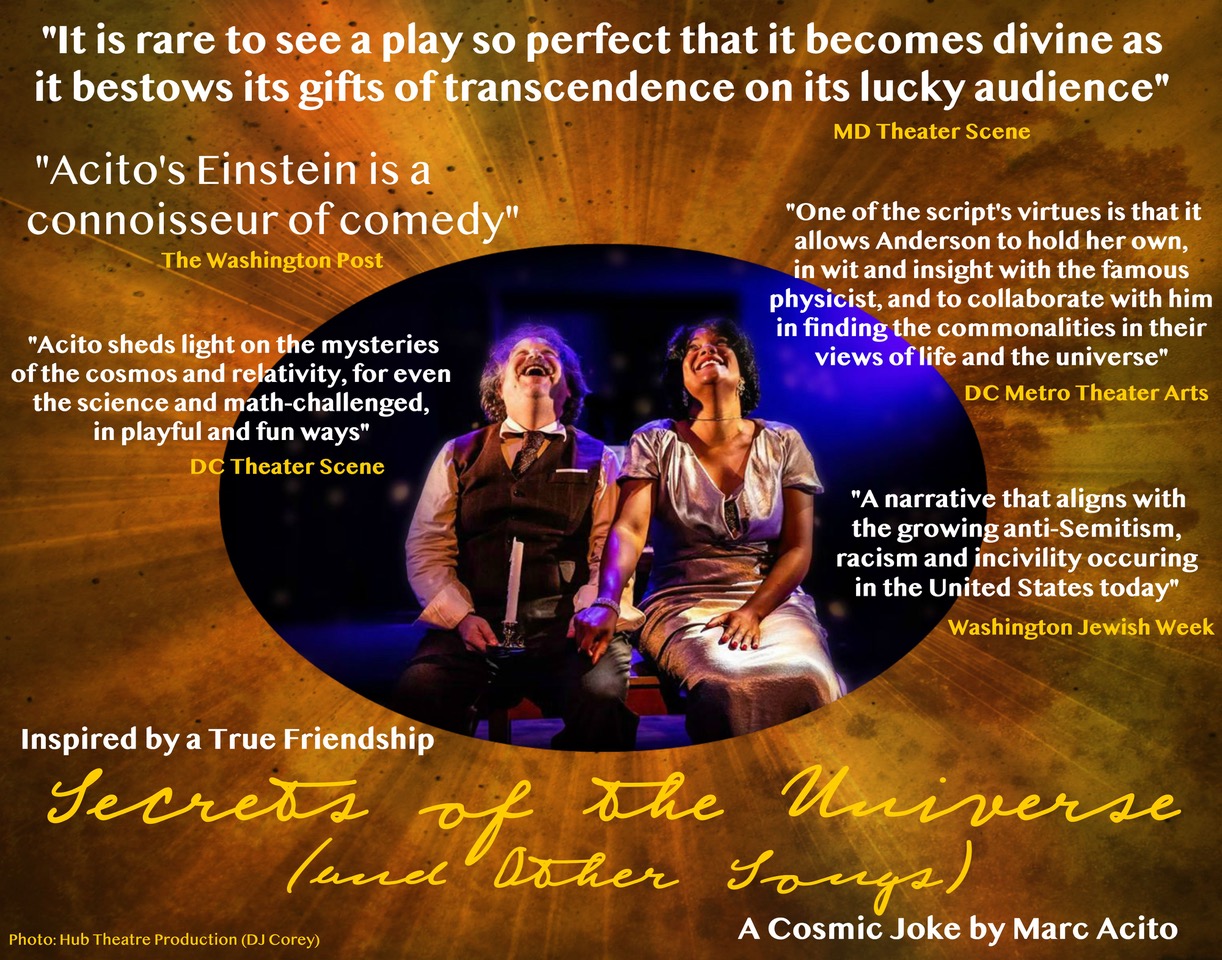

A lot has been going in with you in the past year. Your play The Secrets of the Universe (and Other Songs) about the relationship between Albert Einstein and Marian Anderson had a full production at the Hub Theatre in Fairfax, Virginia last July. Did that live up to your expectations? Did anything about that production inform your revisions to THE SPACE RACE?

That production emboldened me as a surrealist. What was so enlightening was how audiences embraced the weird and esoteric from the very moment the play hopped out of naturalism and into the psyches of the characters. The first tier critics didn’t understand it, so they were hostile, which made me realize I need to do a better job communicating my mission as an artist. What was most gratifying was the response of black audiences. As a gay, white man I’m highly sensitive to the perils of writing about the intersectionality of oppressed minorities. So I was thrilled when, during a talkback, a black man in the audience said he was surprised to discover I was white.

How great is it that there is a German song about Alabama? At what point in the writing of MAN IN THE MOON did you realize how you were going to use the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill song “Moon over Alabama” (aka “Alabama Song (Whisky Bar)”)?

The idea came very late in the process, which I find astonishing considering I did my college thesis on Weill. I wrote the play while listening to Wagner, occasionally switching to Haydn’s Creation. When I got the idea to begin the play with “Fly Me to the Moon” in Russian, I instantly thought of using “Moon Over Alabama” and “Stars Fell on Alabama.”

You’ve developed plays and musicals with many different theatrical organizations. How is the EST/Sloan Project play development process different?

As someone who coaches writers, I’m shocked at how rude and insensitive some theater professionals can be when giving notes. Linsay Firman and Graeme Gillis do it right. They organize their thoughts into a digestible size; they ask legitimate questions rather than question-shaped opinions; they focus on what resonates for them as much as what eludes; and they truly seem to hold writers in high esteem.

What’s next for Marc Acito?

A complete departure. I’m back to comedy roots directing a staged concert at the York Theater of the little-known Lerner and Loewe musical The Day Before Spring, which I adapted. It’s like a Doris Day/Rock Hudson romcom—February 9 through 17—the perfect date night for Valentine’s Day.

The 2019 EST/Sloan First Light Festival runs from January 28 through March 1 and features readings and workshop productions of ten new plays. The climax of every EST/Sloan season is the annual Mainstage Production, which this year was the world premiere of BEHIND THE SHEET by Charly Evon Simpson. Directed by Colette Robert, BEHIND THE SHEET confronts the history of a great medical breakthrough by telling the forgotten story of a community of enslaved black women who involuntarily enabled the discovery. Previews began January 9 and the show runs through March 10. Tickets can be purchased here. The First Light Festival is made possible through the alliance between The Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, now in its twentieth year.

Portions of this interview appeared on this blog previously when MAN IN THE MOON had a reading during the 2018 First Light Festival.