What motivates someone to become an activist? And what sustains the energy of that activism? Biologist Rachel Carson was already an acclaimed nature writer when she decided she must write about the dangers of pesticides. In her riveting new play SPRAY, Emily Chadick Weiss focuses on the last eight years of Carson’s life, when her work on her classic bestseller Silent Spring coincided with the first deep relationship of her life, her new role as an adoptive mother, and her enervating battle with cancer.

SPRAY will have its first public reading at 3:00 PM on December 12 at the Ensemble Studio Theater as part of the Fall 2024 EST/Sloan First Light Festival. The reading is free and reservations are encouraged.

We spritzed Emily with questions about her play. She showered us with answers.

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

How did SPRAY originate?

I found a postcard collection that featured various female scientists and after reading about each one, I found Rachel Carson’s story the most fascinating. That was probably back in 2017. I’ve been tinkering with how to dramatize her legacy ever since.

What kind of research did you do?

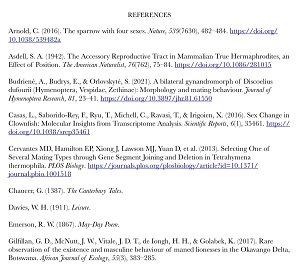

I focused on her biography, Rachel Carson, Witness for Nature by Linda Lear, the book of letters with her friend Dorothy Freeman, Always Rachel, and her groundbreaking book, Silent Spring.

Were you able to find Rachel Carson’s voice in her writing?

I don’t know if I captured Rachel’s voice in this play but I hope I captured her intention — both to save nature and humanity by reducing our reliance on chemicals and to have company in her quest by connecting so frequently over letters with her close friend Dorothy Freeman.

It’s estimated that Rachel and Dorothy Freeman exchanged some 900 letters over their lifetime. How would you characterize their relationship?

I believe they had the most romantic relationship over their letter correspondence but we’ve only been able to read the non-romantic letters since they hid the “apples” elsewhere …

Rachel’s mother Maria is also in the play. She kindly typed all of Rachel’s books. What was their relationship like?

In Linda Lear’s biography of Rachel, Maria is portrayed as being envious of Rachel’s close relationships with other people. But I think Maria was also very encouraging of Rachel’s academic passions, especially since they were unusual for a woman in the years up to and including the 1960s.

Did your experience as a writer for the PBS children’s show “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood” help in creating Roger, Rachel’s 5-year-old nephew?

I would say my experience raising a young boy, Robin, now 6, helped me find a place for the presence of Roger in the play. “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood” does help me raise Robin, however!

Did you discover anything surprising about Rachel Carson as you wrote SPRAY?

Throughout my research and writing of SPRAY, I have been in awe of how much Rachel put on her plate — not only did she make a point of publicizing her research on dangerous pesticides to the world in a very controversial way, but she also raised her niece and great nephew when no one else could take care of them, despite her never wanting children.

Why this play? Why now?

We should be aware of all climate change heroes even if humankind is not capable of saving itself.

What do you want the audience to take away from SPRAY?

I’d like us all to come away thinking about what we fight for and don’t bother to fight for. I’d like people to see some of the highs and lows of Rachel Carson’s life and perhaps learn more about her as they ride the train, read their phones, etc.

What do you see as Rachel Carson’s legacy? What should people know about her today?

Rachel Carson is one of the early activists in the environmental movement of the 1960s. JFK started enacting legislation because of her book Silent Spring.

What is your favorite experience of nature?

The yearly surprise of leaves changing color in the Fall, the magic of rainbows and double rainbows, a clear view of the billions of stars at night, and the humbling repetition and volatility of the ocean.

You were a member of EST’s Youngblood program for eight years. What impact did that have on how you write plays – and on your playwriting career?

I discovered I love writing ten-minute plays and I often conceive new ideas in the ten-minute format. It can be satisfying to write just a moment vs. an entire journey.

The New York Times included “The Fork,” your contribution to the 2017 EST Marathon of One-Act Plays, in its 2021 retrospective, “How Theater Stepped Up to Meet the Trump Era.” I was among those who joined in what the Times describes as the “delighted, unhesitating laughter” at a comedy about killing the president. The reviewer found that response “as jarring at the time as it was telling about the state of our civic health.” What do you have in store for the former president’s new term?

I do have a sequel in mind for “The Fork”…

What’s next for Emily Chadick Weiss?

I’ll probably be writing about another exceptional female scientist soon, and finding homes for my plays, TV and films. I pray that in 2028 or in my goddamn lifetime, I will be someone who voted in our first female president.

SPRAY is one of three readings of new plays in development as part of the EST/Sloan Project in the Fall 2024 First Light Festival, which runs from October 24 through December 12. The festival is made possible through the alliance between the Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.