The 2015/2016 EST/Sloan First Light Festival continues this week with Roughcut Workshops on January 13 and 14 of THE ICE (previously entitled BUILDING TWENTY-TWO) by Cory Finley, a member of Youngblood at EST. In 2015 the Flea Theater produced the world premiere of Finley’s The Feast, to considerable acclaim.We recently peppered Finley with questions about his new play.

THE ICE deals with the increasingly intense interactions among three scientific researchers in a remote American outpost, much like McMurdo, in Antarctica. What kind of research did you do to write the play? Did you consult with any scientists?

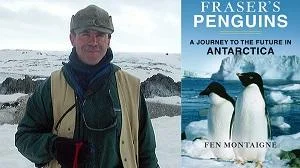

I've been trying to get down to Antarctica myself. No dice, yet – it's a complicated travel proposition and there's significant red tape, unless you're just there on a guided penguin cruise. I did speak with several scientists who've been to McMurdo, to the smaller Palmer station, or to both. The writer Fen Montaigne, who traveled to Antarctica for his great book Fraser's Penguins, talked to me about the continent and then connected me with Dr. Hugh Ducklow, principal investigator of the Palmer Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) project, who in turn set me up on the phone with Dr. Diana Wall and Dr. James McClintock, author of Lost Antarctica – all scientists with long track records of fascinating research on the continent. They were all extremely generous with their time, and our conversations gave me a sense of how research in Antarctica works and some of the peculiarities of base culture. I also read several books about the continent and the experience of working on the support staff there. I set the play in a fictional base to give myself more freedom to tell the story I want to tell, but the world of the play is shaped by this research.

THE ICE seems to be as much about the power dynamics between the three researchers as it is about the science. Did you base this aspect of being a working scientist on what you’ve heard from or read about any actual scientist or scientists? Or did you perhaps simply extrapolate these interactions from your own experience?

I think desperate circumstances have a way of revealing character, and Antarctica is already a physically extreme place, so it felt right to jack up the stakes of this fictional research season to match. And of course that pushes the characters to some dark corners of their psychology.

But no, none of the scientists told me about the sorts of mind games that get played in this story. And I doubt that any real research team at McMurdo or Palmer has ever gone through a research season as hellish – although there was a famous case of a Soviet researcher at Vostok in the 1950s who attacked a chess partner with an axe.

What I do know is that scientists are passionate, driven people working in a competitive field with limited resources, and that is a dynamic I know well!

One of the sources of tension in the play is that scientific research can involve hours of boring data entry or it can involve discovering something never yet seen before – and it may not be clear at the outset which will deliver the more significant results. Is that a point you set out to make or was it something that emerged as the play developed?

Yeah, absolutely – the way scientists spoke and wrote about the scientific process reminded me a lot of my own creative process: there are a few thrilling moments when it all comes together, but in between those moments is a long, dull, and often fruitless slog. To succeed in either field you have to find the pleasure and even the beauty in the work itself, not in the results it might or might not produce.

I often wonder, though, if there's a temptation to become too devoted to the work itself. A sort of religious devotion to the slog that can make you forget why you started slogging in the first place. It can be psychologically healthy to say to yourself, “I'm not doing this for the acclaim / the splashy publications / whatever; I'm doing this because it brings me joy, in all its difficulty.” But can that be a defense mechanism that keeps you from doing great things? The play has been, among other things, a way of staging my own internal combat about these questions.

You set the play in October, the first month of the Antarctic summer, when there are twenty-four hours of sunlight. How much of an impact do you think this has on your characters?

I think it's huge! I love that feature of the environment, and originally I wanted to set the play in the Antarctic winter, for the creepiness of the 24-hour darkness. But I think it's a lot more interesting to have a play that takes place in what feels like a month-long day...I like that the characters are stuck in an unchanging present and subconsciously waiting for the relief of a night that never comes.

How is writing a play about science different from writing a play not about science? What makes scientists different?

Well, at the end of the day, scientists are complex, contradictory people who want respect and love and power – just like any other characters. I do think that so often, we see scientists in dramatic stories as either nerds with goofy ideas or these mythic figures, led by a series of surprising but inevitable clues in the world around them toward their history-shaping discovery. My goal here was to write a play that dramatized all the frustrations, petty conflicts and banalities of the scientific process, but ultimately showed how, through hard work and investment, scientists can quietly rise above all of that.

The First Light Festival is a three-month-long series of workshop productions and readings that is part of the play development process of The EST/Sloan Project, a joint venture of the Sloan Foundation and the Ensemble Studio Theatre. Roughcut Workshops of THE ICE will take place at EST on January 13 and 14 at 7 PM. Tickets are free, but reservations are required. To reserve tickets click here.